Arithmetic and Mathematics

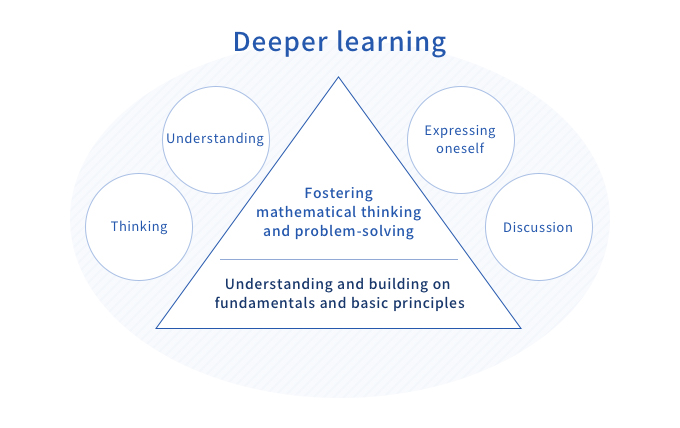

Goals of Arithmetic and Mathematics

- 1To train students to express their own ideas and try and understand the ideas of their friends.

- 2To train students who are capable of thinking persistently until the very end, without giving up.

Points of focus

- To get students to enjoy arithmetic as a whole class as they deepen their understanding.

- Get students to expand their view of the world of arithmetic by using their existing knowledge to tackle problems from a variety of angles, and logically clarifying how things work.

- Through dialogue and discussing their opinions with each other, students become aware of ways of seeing and thinking that they would not otherwise come up with. Students feel delighted when their ideas are accepted by their friends and when they understand their friends’ ideas.

- Building on the skills they master through their thinking and discussions, students learn to independently identify new problems, tackle them with persistence, and solve them on their own.

- Students develop mathematical thinking and problem-solving skills by working to understand and build on fundamentals and basic principles.

- The higher a mountain, the wider its base. Likewise, when studying arithmetic, knowledge is built up on top of what has been learned. Therefore, students work carefully and slowly to develop a solid understanding of the fundamentals and basic principles of arithmetic.

- We believe that mathematical ways of thinking and problem-solving skills to discover mechanisms and rules and to solve problems are important foundations of arithmetic.

- We always design our classes based on a clear awareness of how we want students to think, what we want to teach them, and what we want them to master.

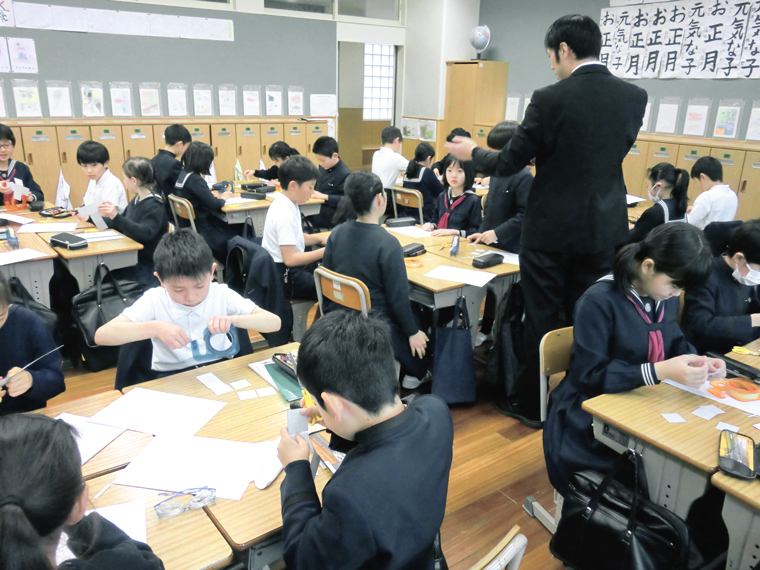

Classroom scenes

Fractions and multiples (Grade 2)

After being presented with three strips of tape, students were asked to think about the relationship between them. The tapes were not marked with their lengths. The aim was not to find the lengths of tapes, but to consider how long a tape appears to be when one of the other tapes is defined as having a length of “1.” When the three strips of different lengths were shown to them, the students naturally tried to compare their lengths, even without knowing the measurements of any of the tapes.

The children offered their estimations.

“B looks twice as long as A, more or less.”

“C is about four times longer than A… or even longer.”

The concept of “times” learned in multiplication was applied. Students were able to estimate the lengths of B and C by referencing the shortest tape, A.

Later, by laying the pieces of tape over each other, the students learned that B was twice as long as A, while C was six times longer than A. At this point, one student announced, “A must be half as long as B.” A whole new way of seeing things opened up.

“If A is half as long as B, its length is 1/2.”

“If B is twice as long as A, then B is half as long as A.”

These comments triggered a lively discussion. Then, more students began to think similarly about the relationship between A and C.

“If C is six times longer than A, A is one-sixth (1/6) the length of C.”

“What about B and C?”

“If C is three times longer than B, B is one-third (1/3) the length of C.”

Finally, they used the strips of tape on the blackboard to check whether their estimates were correct.

A student raised a hand.

“If I look at the two pieces of tape and say that the longer one is x times longer than the smaller one, then the smaller one is 1/x times the length of the larger one.”

The students now understood the relationship between the lengths of the two tapes. They were able to connect the ideas of fractions and multiplication. Through problem-solving exercises like this, students discover new challenges, and by tackling them with interest, their ability to see and think mathematically improves.

“Nets of a Cube” (Grade 4)

The students considered what the surfaces of a cube would look like if they were unfolded into two dimensions. First, they made 3D cubes by attaching six pieces of cardboard together with adhesive tape. They then peeled off the tape at various edges to unfold the cubes. In groups, students then discussed what the nets would look like.

When all the groups traced the nets onto drawing paper and arranged their work on the blackboard, students noticed various things. “A’s net is the same as B’s net.” “These two nets are the same if one of them is reversed.” To facilitate the study of congruent shapes taught in Grade 5, the teacher explained that if the nets were rotated or turned over and laid over each other, it became evident that some shapes were the same. Even nets that were different could be organized according to their similarities. In one pattern (1, 4, 1), there was one square (one cube surface) on the left, four in the middle, and one on the right. There was also a 2, 2, 2 pattern. One student commented, “Even without assembling, you can see that two sets of an L-shape made with three squares will form a cube.” Students also created nets with patterns of 2, 3, 1 and 3, 3, and eventually, through the efforts of the whole class, all 11 nets were identified.

Through classes like this, we aim to foster independent, interactive, and deep learning.

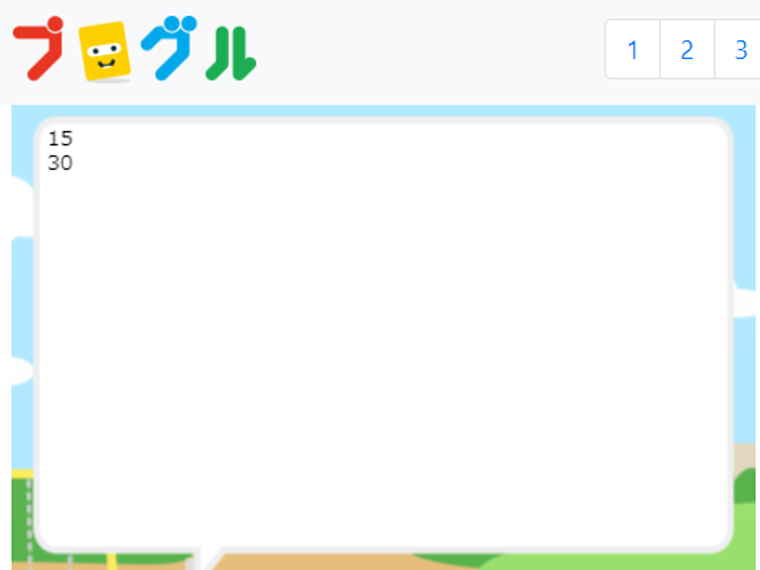

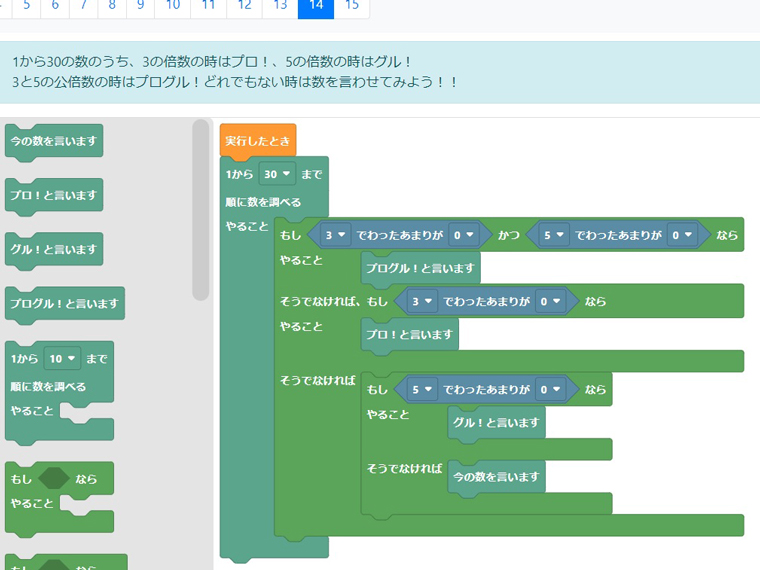

“Multiples and Common Factors” (Grade 5)

This is a Grade 5 class on multiples and common factors. After learning a basic method of finding multiples and common factors, students created a simple computer program to find multiples and common factors.

As humans, when we examine the characteristics of whole numbers, we can find multiples of 3 and multiples of 5, respectively. Any number in common, i.e., a number that is a multiple of both 3 and 5, is called a “common multiple.” The computer program created by the students works differently. It counts numbers in order starting with 1 and asks for each number, “Is this a common multiple of 3 and 5?” If the answer is no, it asks, “Is this a multiple of 3?” If the answer is no, it asks, “Is this a multiple of 5?” If the answer is no again, the number is neither a multiple of 3 nor a multiple of 5, so it obviously cannot be a common multiple of 3 and 5. Following this logic process system, the computer sifts through whole numbers in order from one to the next. Some students noticed a difference between the ways that humans and computers think. Humans start with easy conditions and gradually make them stricter, whereas computers start with strict conditions and then make them looser. One student who was having difficulty said, “I was able to do it by reversing the order.” It is also important to learn how to think about correcting programs when they do not work as expected. Through these experiences, the students learned how important it is to understand the difference between human and computer thinking. They realized that for a computer to work correctly, humans need to think about and create the program very clearly and carefully. At the same time, they developed a deeper understanding of multiples and common factors. Some of them, who had gained experience and deepened their understanding, thought, “I want to try it with bigger numbers”.

The students realized that problems need to be solved in a step-by-step process and that when there is a task that requires simple repetition, computers allow us to quickly investigate a large selection of numbers. They also learned about the characteristics of programming procedures.

In this way, while using computers at certain times, students develop the ability to think logically (computational thinking).