y157Εz

Lessons

from the Inoue Zaisei and the Takahashi Zaisei

Kikuo Iwata, Yasushi Okada, Seiji Adachi and Yasuyuki Iida

Introduction1

Since the 1992 recession, the performance of the Japanese

economy has been the worst of the developed nations. Japanfs average rate of

real economic growth was only 1.1% between 1992 and 2001, compared with 4.0%

growth in the 1980s. The comparable figures for

A number of hypotheses have emerged, including the

inadequacy of fiscal policy, inappropriate monetary policy leading to

deflation, the low investment rate following over-investment during the bubble

period of the late 1980s and early 1990s, financial disintermediation due to

huge nonperforming loans, and a fall in the potential growth rate because of

supply-side factors.

In an attempt to repair the economy, the then Prime

Minister Keizo Obuchi from

1998 until 2000 substantially increased government expenditures and cut both

income and corporate taxes. The result was a huge increase in the stock of

government bonds. In contrast, for the past three years, the then Prime

Minister Junichiro Koizumi from 2001 untill 2006 largely reduced government expenditures and

tried to improve the supply side of the Japanese economy. Koizumi was confident

that regulated and inefficient public enterprises and financial corporations

were responsible for Japanfs poor performance in the 1990s. Therefore, he

intended to regenerate the Japanese economy by implementing structural reforms,

including deregulation and privatization of public enterprises and financial

corporations. Such economic reforms were undertaken in developed countries such

as the

However, we doubt whether the structural reforms

succeeded in regenerating the Japanese economy. There had been a large

deflationary gap in the Japanese economy since 1998, and it was highly likely

that the structural reforms enlarged this gap by raising the potential growth

rate. If so, it is less likely that the structual

reforms are the cause of the economic recovery since 2002.

It should be noted that the developed countries,

including the

No country had experienced deflation in the postwar

period until the Japanese economy did so in 1998. However, in the 1930s, many

countries, including

This paper examines the Takahashi Zaisei

in order to throw light on the causes of the prolonged stagnation

1 How

1-1 The Inoue Zaisei

that caused the Shouwa Kyou

Kou

Inoue Zaisei

as a Deflationary Regime

We evaluate economic policies from the perspective of the

policy regimes adopted by policy agents. A policy regime is the framework that

determines the rules of the game in which economic agents participate. It is

systematic and hence predictable. Economic agents would not respond to policies

that are inconsistent with the policy regime, but only to those that are

consistent with it.

Then, we examine which policy regime resulted in the Shouwa Kyou Kou(the

Shouwa Great Depresion).

From the outbreak of World War I in 1914 until 1919,

the Japanese economy boomed because of a huge trade surplus. However, at the

end of the war, the trade surplus was reduced rapidly and

The then Minister of Finance, Jyunnosuke

Inoue, who took office in 1929, was confident that structural y159Εzproblems gave

rise to the prolonged stagnation of the 1920s. He believed that inflation

should have been lowered, the exchange rate increased, and inefficient firms

liquidated. Therefore, he decided to appreciate the exchange rate to its prewar

level by returning to the gold standard system that had been suspended since

the beginning of the WWI. In addition, he adopted tight monetary and fiscal

policies in order to lower the general price level. The end result was the Shouwa Kyou Kou. This economic

policy is called Inoue Zaisei (Inoue Economic Policy)

after the Minister of Finance.

The Inoue Zaisei policy

regime was one of deflation, based on inefficient firm liquidations and the

return to the gold standard. According to Schumpeterfs creative destruction

hypothesis, creative firms will appear only after inefficient firms are

removed. Inoue believed that the liquidation of the inefficient firms would

allow the Japanese economy to regenerate through the so-called Schumpeterian

process of creative destruction.

1-2 The

Change of the Economic Policy Regime by Takahashi

Takahashi Zaisei

as a Reflationary Regime

As Inoue Zaisei caused an

economic disaster, Tsuyoshi Inukai took over the

reins of government and appointed Korekiyo Takahashi

as Minister of Finance. Takahashi immediately suspended the gold standard

system and then issued public bonds to finance increased public expenditures.

In addition, he had the Bank of Japan buy public bonds directly from the

government. This increased the money supply at the same time as public

expenditures increased. Thus, Takahashifs regime involved not only expansionary

fiscal policy but also easy monetary policy, even though this policy is called

Takahashi Zaisei (Takahashi Fiscal Policy).

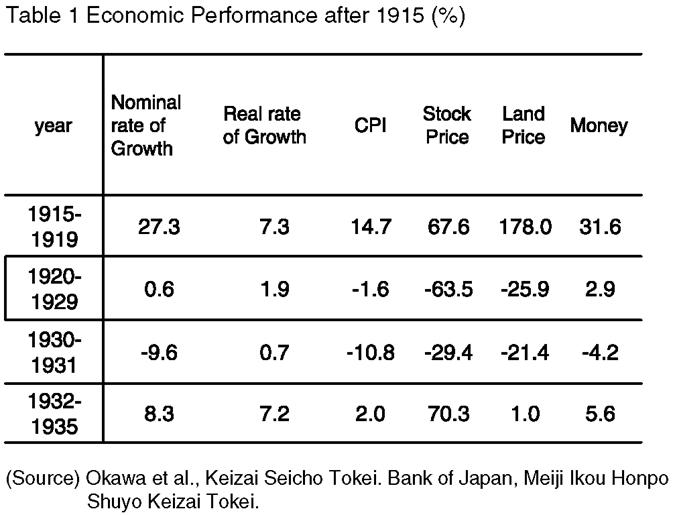

Chart 1 shows that, as the

ratio of public bonds held by the Bank of Japan increased, the deflation ended

and mild inflation developed. The average rate of growth of the money supply

rose from negative 4.2% for 1930-1931 to 5.6% for the period 1932-1935 (see

table 1).

When Takahashi was assassinated in February 1936, the

A Two-Step Change of the Policy

Regime

We trace in detail the process in which the deflation

was ended and inflation developed.

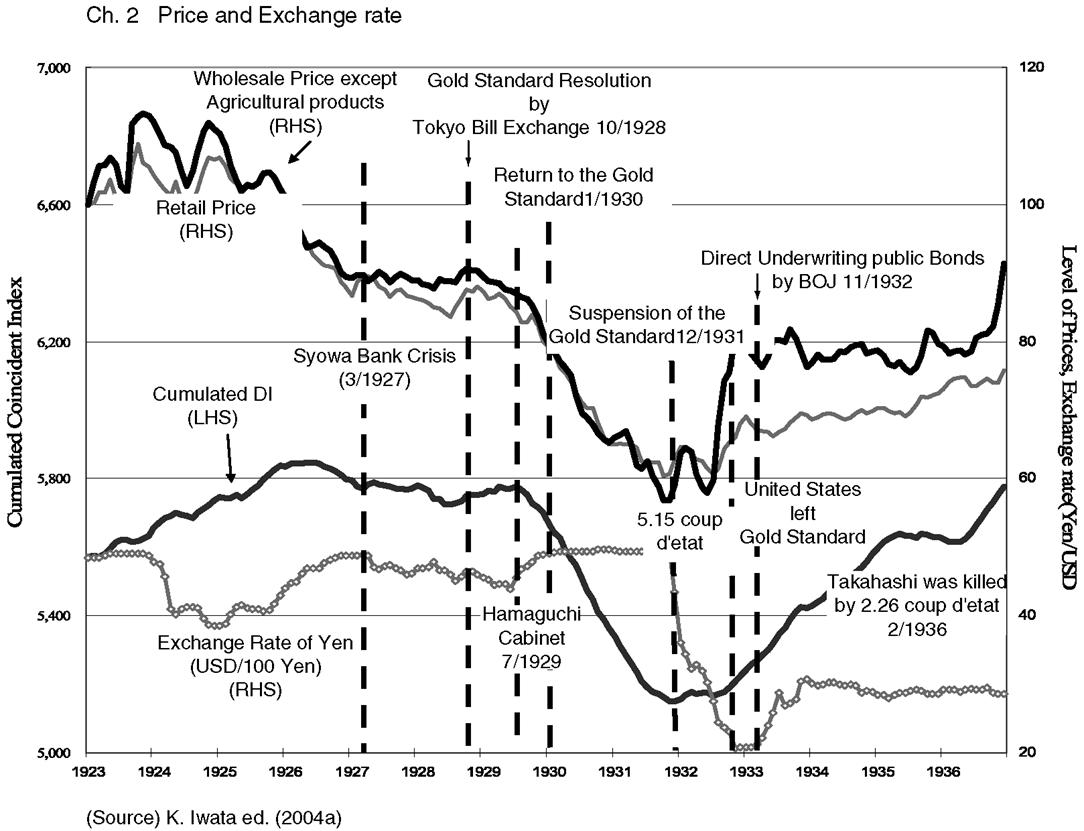

Takahashi suspended the gold standard system on 13

December 1931 and returned to a floating exchange system, with the result that

the exchange rate depreciated from $49 per yen to $20-30 per yen (see chart 2).

The retail price began to rise. Therefore, it seemed that the deflation had

ended. This was the first step of the Takahashi reflationary

policy.

However, some people may have been disappointed that

Takahashi did not take advantage of the suspension of the gold standard to

adopt an easy monetary policy stance. This unrealized expectation may have been

the cause of the decline of stock prices (see chart 3) and the revival of

deflation (see chart 2). Then, on 15 May 1932, the 5.15 coup dfetat occurred, in which then Prime Minister Inukai was assassinated,y160Εz and this was followed by a steep plunge in

confidence about the economy (chart 2).

In November 1932, against the background of these

circumstances, Takahashi resolved to adopt an easy monetary policy under which

the Bank of Japan directly underwrote public bonds issued by the government.

This direct underwriting of public bonds is called a monetization policy. This

was the second step of the Takahashi reflationary

policy and it completely ended the deflation (see chart 2).

The Change of the Expected

Inflation Rate caused by the Policy Regime Change

According to chart 3, the stock price had risen substantially

before the gold standard system was suspended in December 1931. Charts 2 and 3

show that the stock and the retail prices started to rise

in August 1932, before the Bank of Japan began to directly underwrite the

public bonds issued by the government in November of that year. This suggests

that inflationary expectations had already developed before the suspension of

the gold standard system or the start of the direct underwriting of issued

public bonds by the Bank of Japan.

The change of the policy regime to a reflationary regime would first raise the expected rate of

inflation, which in turn would raise stock and land prices, and then the actual

rate of inflation. Finally, both the nominal and the real rate of economic

growth would rise. We investigate further when inflationary expectations

developed under the Takahashi Zaisei.

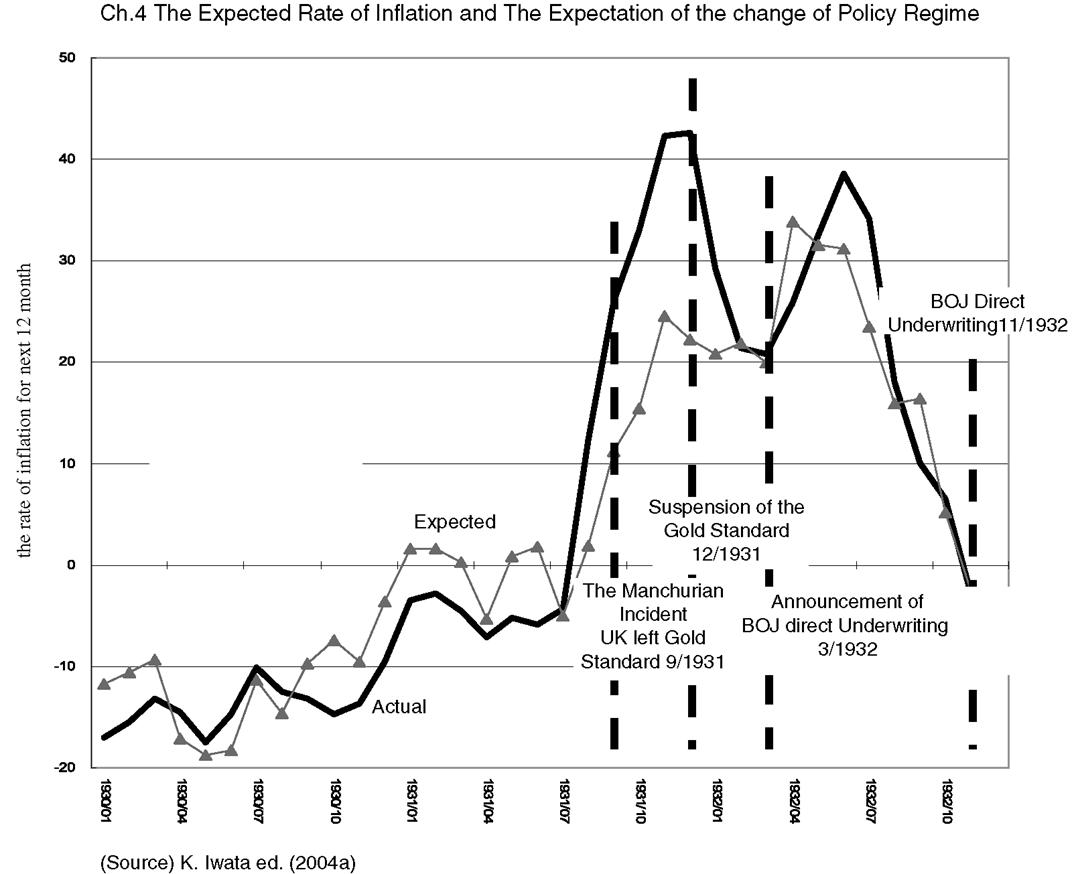

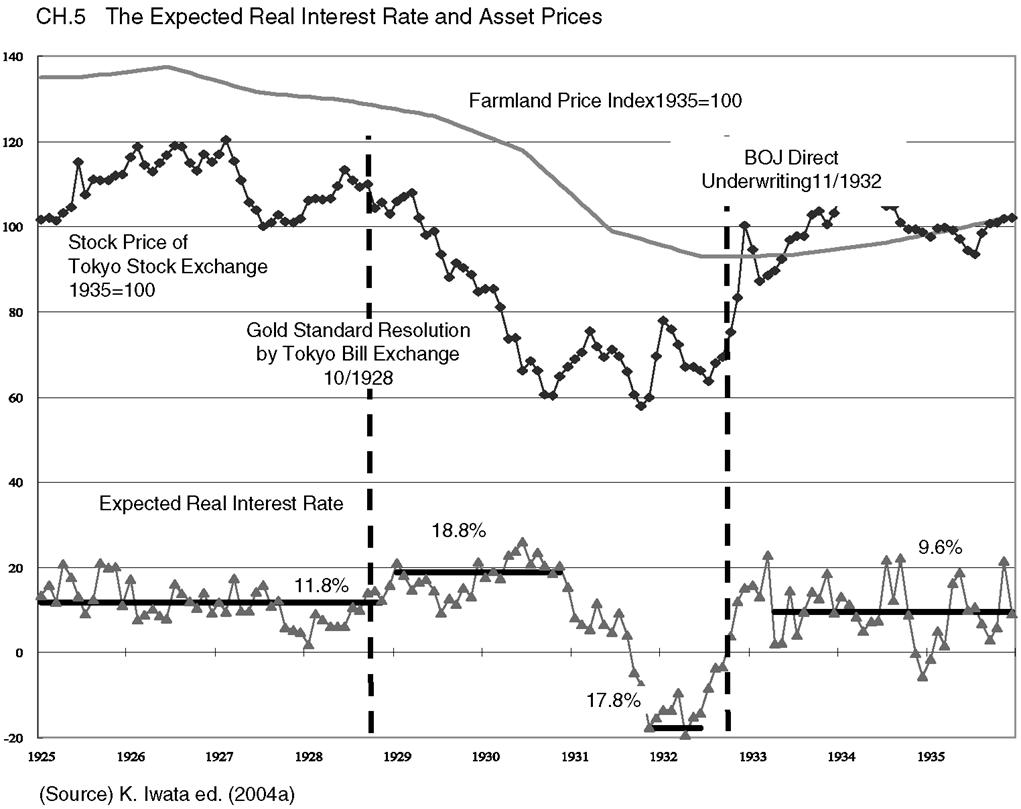

Okada and Iida (2004) estimated the expected rate of

inflation in the 1920s and 1930s by using the interest rate model developed by Mishkin (1992). They found the following:

(1) The

expected rate of inflation rose to a positive figure in September 1931, before

the suspension of the gold standard system in December 1931 (chart 4). In

September 1931, the Manchurian incident broke out and

(2) However,

the expected rate of inflation began to decrease after the suspension of the

gold standard system in December 1931. This may have been because an easy

monetary policy was not adopted. The expected rate of inflation suddenly

increased again in April 1932, after Takahashifs announcement in March of that

year that, in the near future, he intended to adopt the policy under which the

Bank of

The effects of inflationary expectations

Let us consider how the development of inflationary

expectations following Takahashifs reflationary

policy regime stimulated the Japanese economy and saved it from the economic

crisis.

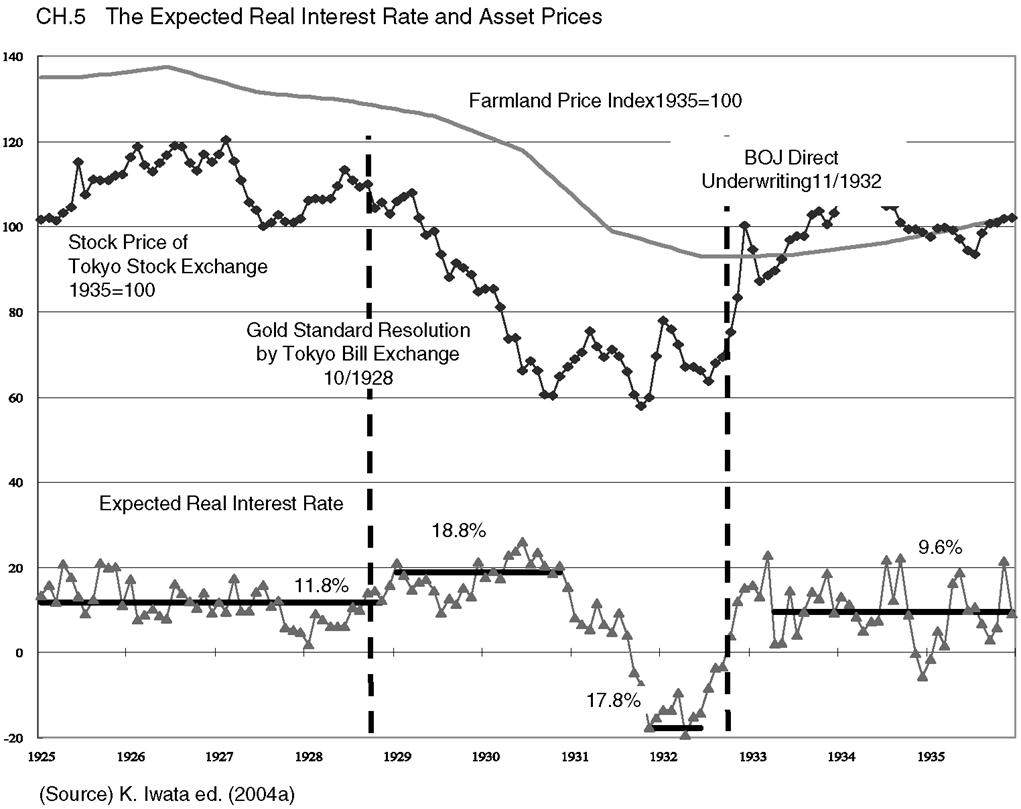

(1) The reduced expected real

interest rate

As long as the nominal interest rate does not rise as

much as the expected rate of inflation does, the expected real interest rate

falls2. Chart 5 shows that the expected real

interest rate during the Takahashi y161ΕzZaisei period was

much lower than just before and during the Shouwa Kyou Kou period.

This reduction in the expected real interest rate

increased both investment and durable consumption expenditures to raise Gross

Domestic Product (GDP).

(2) The improvement in the balance sheet

The increase of the expected rate of inflation raised

stock and land prices (see chart 3). Those increases improved the balance

sheets of firms and households, which may have increased their expenditures.

(3) The increase of equity finance

The rise of stock prices greatly increased

equity finance (see chart 6), which encouraged the establishment of new firms

(see chart 7).

Chart 8 shows that the number of corporations being

established decreased during the deflationary period, whereas it increased

during the inflationary period.

We infer from these facts that the hypothesis of a

Schumpeterian creative destruction process is not supported.

1-3 Other Hypotheses about the

Recovery from the Shouwa Kyou

Kou

We now consider alternative hypotheses about the

recovery from the Shouwa Kyou

Kou.

The Reduced Nonperforming Loans

Hypothesis

It has been claimed that the Japanese economy

stagnated during the 1920s because of the financial disintermediation that

resulted from the huge nonperforming loans. From this point of view, the Takahashi

Zaisei succeeded in regenerating the Japanese economy

only because the Shouwa Kinyou

Kyou Kou (the Shouwa Bank

Crisis, not to be confused with the Shouwa Kyou Kou) removed almost all of the nonperforming loans in

1927.

Adachi (2004) disputed this hypothesis by indicating

that new nonperforming loans increased remarkably during 1930-31 the Shouwa Kyou Kou period, even

though many earlier loans were reduced in 1927.

Chart 9 shows that industrial output increased rapidly

during the Takahashi Zaisei period, whereas bank

loans were reduced. Thus, the financial disintermediation problem was not

solved during the Takahashi Zaisei period. However,

the Japanese economy succeeded in escaping from the Great Depression. The

question is why.

Chart 10 shows that the corporations had abundant

internal funds during the Shouwa Kyou

Kou period and could therefore finance their own investment expenditures.

Another way of financing expenditures was by issuing

equity, as shown above (see chart 10).

Corporations recovering from the Great Depression in

the

y162ΕzThe

Fiscal Policy Hypothesis

Another claim is that the Japanese economy recovered

from the Shouwa Kyou Kou

because of the combined effects of fiscal policy and the Pacific Ocean War.

In July 1935, Takahashi made the following comments on

the public bond policy:

(1) A

large amount of public bonds have been issued since the 1932 fiscal year. So

far, this public bond policy has resulted in a decline of the interest rate

aimed at restoring the economy.

(2) However,

we will not be able to issue public bonds to the extent that we have done in

the past. Excess issues cause an inflationary spiral and financial bankruptcy,

as shown by the experiences of European countries after WWI.

Charts 13 and 14 show that both the military

budget and the balance of long-term public bonds increased considerably in

fiscal years 1932 and 1933, during the first half of the Takahashi Zaisei. However, the growth rates of both decreased

substantially in fiscal years 1934 and 1935, the second half of the Takahashi Zaisei.

As the Japanese economy had already recovered from the

crisis by 1933, Takahashi attempted to reduce the government budgets from that

fiscal year. In February 1936, he was assassinated in the 2.26 coup dfetat by the military, which strongly demanded an increase

in its portion of the budget.

The next Minister of Finance, Eiichi Baba, adopted an

inflationary economic policy that increased the military budget as much as the

military demanded. He had the Bank of Japan directly underwrite public bonds to

finance the budget.

Charts 13 and 14 show that both the military

budget and the balance of long-term public bonds increased enormously after the

end of the Takahashi Zaisei in the 1935 fiscal year.

The average rate of real economic growth was 4.5% and

inflation was around 10% for the period from 1936 to 1940, whereas these rates

were 7.2% and 2.0%, respectively, during the Takahashi Zaisei.

The ratio of real consumption expenditures to real GDP, which indicates living

standards, dropped to less than 60% in 1940, whereas it was about 72% during

the Takahashi Zaisei.

Hence, we conclude as follows:

(1) The

fiscal policy hypothesis that the Takahashi Zaisei

succeeded in recovering from the Shouwa Kyou Kou by a huge increase in the fiscal budget is not

supported.

(2) The

Pacific Ocean War did not finally save the Japanese economy from the Shouwa Kyou Kou. Instead, it

completely ruined the economy.

2 Lessons from the Shouwa Kyou Kou

We now consider what lessons we should learn from the Shouwa Kyou Kou that may throw

light on the causes of the prolonged stagnation of the Japanese economy in the

1990s and early 2000s, and what policies will sustain and stabilize growth.

Why the Takahashi Zaisei Succeeded

As long as deflationary expectations exist, the

expected real interest rate may not decrease to levels necessary to increase

both investment and durable consumption expenditures. This is due to downward y163Εzrigidity in

the nominal rate of interest. In addition, deflationary expectations may

decrease both the stock and land prices, worsening the balance sheets of firms

and households, with the result that their expenditures will decline.

Therefore, to restore the economy from stagnation, which arises from persistent

deflationary expectations, and to return to sustained and stable growth, the

expectation of deflation itself must be removed.

Section 1 shows that the reasons for the

success of the Takahashi Zaisei were the suspension

of the gold standard system accompanied by the direct underwriting of public

bonds by the Bank of Japan. This definite change of the policy regime to

a reflationary regime raised the expected rate of

inflation and stimulated the economy, as shown in section 1-2.

Eichengreen (1992) and Bernanke (2000) showed that the

If the persistent expectation of deflation is removed and

an expectation of mild inflation is established, the macroeconomy

would become stable. To change expectations, it is essential that the policy

regime is credible. Therefore, the policy agents should be strongly committed

to maintaining their policy regimes.

Policies for Sustained Economic

Growth

Since 1992, there have been fierce debates among

economists about the causes of Japanfs stagnation. These arguments, which have

continued for more than 10 years, can be categorized into two broad theories:

first, the argument that Japanfs structural problems were the cause of the

stagnation, and second, the argument that the Bank of Japanfs monetary policy,

which induced deflation, was to blame. In assessing the validity of these

arguments, it is worthwhile to reflect on these theories in the light of the

recovery from the Shouwa Kyou

Kou, as well as the more recent recovery that has occurred since 2002.

There are variations within the broad theory that

structural problems are the cause of the stagnation. The most typical argument

is that the banks were to blame because they were reluctant to advance new

loans, and extended forbearance lending. If the reluctance of banks to lend was

indeed the cause of the stagnation, economic recovery would require an increase

in the volume of bank loans. However, the Japanese economy began to recover in

2002, despite the fact that bank loans had been decreasing (chart 16). That is,

the recent recovery was achieved without an increase in bank lending, as was

the recovery from the Shouwa Kyou

Kou, and that of the

According to the proponents of the forbearance-lending

hypothesis, the economy remained suppressed as funds were absorbed by

forbearance lending and were unavailable to new businesses. However, during the

recovery of 2002-2004, sound firms utilized their own funds (chart 17). In

fact, firms in general repaid their bank loans just as firms did during the

recovery from the Shouwa Kyou

Kou and the Great Depression (charts 10 and 11).

Some supporters of the structural-problem hypothesis

claim that the recovery of 2002 was a result of the Koizumi reforms. However,

the Koizumi reforms were limited to laying the groundwork for privatization of

the Housing Loan Corporation and the Japan Highway Public Corporation during

2001-2004. It is difficult to relate those decisions to the recovery of the

economy. In addition, it is argued that the Koizumi governmentfs cuts in public

spending aided the recovery by encouraging the self-reliance of loy164Εzcal regions.

However, this is not a convincing argument.

Before examining the theory that deflationary

expectations caused the prolonged stagnation, we must correct the common

misconception that the economy cannot recover while deflation persists. There

are countless cases in history when relatively high growth was achieved in a

deflationary environment. The recoveries from the Shouwa

Kyou Kou and the Great Depression began before

deflation ended. In

Section 1 shows that it is necessary for

public sentiment to change from anticipating deflation to expecting inflation. This study

points to the necessity of a decline in expected real interest rates to a level

compatible with the realization of full employment, which in turn sets the

basis for sustained and stable growth. Hence, if deflation has not ended, but

the anticipation of future deflation ceases, or inflationary expectations

develop, expected real interest rates would fall, bringing about real economic

recovery. That is, we should distinguish between actual deflation and the

expectation of deflation. What is relevant to the performance of the macroeconomy is not actual deflation, but the expectation

of deflation.

Analyses of the behavior of the inflation-indexed

government bonds in the market indicated changes in 2006 in peoplefs sentiment

toward the future, in that they seemed to sense an end to the deflationary

trend. The reasons for this calming of deflationary sentiment were the heavy

intervention in the foreign exchange market by the Ministry of Finance that

occurred in 2003, and clear indications by the Bank of Japan that it was

committed to breaking away from deflation. The remarks by BOJ Governor Fukui

expressed a strong commitment to the fight against deflation, which had been

unexpected given Fukuifs words and actions before assuming the governorship.

However, despite this positive development, the expected

real interest rate has not yet reached the levels required to realize full

employment. For the expected real interest rate to drop to the required level,

inflationary expectations need to rise to around 2-3%. Therefore, the BOJ

should pursue an inflation target and show a strong commitment to attaining a

level of inflation within this range.

References

Adachi, Seiji(2004)hThe Problem of nonperforming loans

and the Transformation of the

Financial System during the Shouwa Great

Depressionh, in Kikuo Iwata, ed., Studies on the Shouwa Great Depression, Touyoukeizai Shinpousha, 2004 (in

Japanese).

Bernanke, B (2000) Essays on the Great Depression,

Bernanke, B (2003) gSome Thoughts on Monetary Policy in

Japan,h before the Japan Society of Monetary Economics, Tokyo, Japan, May, 31

Bernanke, B and Mark Gertler (1989) gAgency Costs, Net worth, and Business

Fluctuations,h American Economic Review,

Vol.79,No.1.

Bernanke, B and Mark Gertler (1990) gFinancial Fragility and Economic

Performance,h Quarterly Journal of

Economics, Vol.105, No.1.

y165ΕzBernanke, B and Mark Gertler (1999) gMonetary Policy and Asset Price Volatility,h

Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank

of Kansas City, Forth Quarter.

Bernanke, B, et al. (2000) gDiscussion,h

NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2000,

Cabarello, Ricardo and Mohamad Hammour (2000) gCreative

Destruction and Development: Institutions, Crises, and Restructuring,h NBER Working Paper Series, No.7849.

Cecchetti, Stephen (1992) gPrices

during the Great Depression: Was the Deflation of 1930-1932 Really

Unanticipated?h American Economic Review,

Vol.82, No.1.

Eichengreen, Barry

(1992) Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard

and the Great Depression, 1919-1939,

Fisher, Irving (1933) gDebt-Deflation Theory of the

Great Depression,h Econometrica,

Vol.1, No.4.

Hamilton, James (1992) g Was the Deflation during the

Great Depression Anticipated?: Evidence From the Commodity Market,h American Economic Review, Vol.82, No.1.

Iwata, Kikuo, ed. (2004a), Studies on the Shouwa

Great Depression, Touyoukeizai Shinpousha, (in Japanese).

Iwata, Kikuo(2004b)h Lessons

from the Shouwa

Great Depression,h in Iwata, Kikuo, ed., Studies on the Shouwa

Great Depression, Touyoukeizai Shinpousha , 2004 (in Japanese).

Kiyotaki, N and John Moore

(1997) gCredit Cycles,h Journal of

Political Economy, Vol.105, No.2.

Krugman, Paul (1998) g Itfs Baaack: Japanese Slump and the Return of the Liquidity

Trap,h Brookings Papers on Economic

Activity, 2.

Mishkin, Frederic (1981) g The Real Interest Rate: An Empirical Investigation,h in K.

Brunner and Allan Meltzer, ed., The Cost

and Consequences of Inflation, Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on

Public Policy, Vol.14.

Okada, Yasushi and Yasuyuki

Iida (2004) gThe Shouwa Great Depression and an

Empirical Investigation into the Real Interest Rate,h in Kikuo

Iwata, ed., Studies on the Shouwa Great Depression, Touyoukeizai

Shinpousha, 2004 (in Japanese).

Romer, Christina (1992) gWhat Ended the Great Depression,h Journal of Economic History, VOL.92,

No.4.

Sargent, Thomas (1982) gThe

End of Four Big Inflations,h in Robert Hall, ed., Inflation: Causes and Effects,

Temin, Peter (1989) Lessons from the Great Depression,

y166Εz

y167Εz

y168Εz

y169Εz

y170Εz

y171Εz

y172Εz

y173Εz

y174Εz

y175Εz

y176Εz

y177Εz

y178Εz

y179Εz

y180Εz

y181Εz

y182Εz