y181Εz

Family

Ownership, Investment Behavior,@and Firm Performance

——Evidence

from Japanese Electric Machinery Industry——

Shigeru Asaba and Eiji Kunugita

Abstract

We studied family firms in the

Japanese electric machinery industry.

First, we compared firm performance between family and non-family firms,

and found that family firms show higher profitability. Second, we tried to distinguish among

reasons for better performance of family firms. The results of several t-tests and

regression analyses suggest that selecting top management from the pool

restricted to the family is not an important disadvantage of family firms. They also suggest that neither combining

ownership and control nor holding large equity share is the advantage of family

firms. On the other hand, family

firms in the sample invest in capacity significantly more than non-family firms

in the 1990s. Therefore, longer

investment horizons of family firms may be the reason for better performance,

especially during the low growth era.

TDIntroduction

In contrast to Berle and Means's view that

ownership is separated from management in modern corporations, several studies

reported that family-owned firms are prevalent in the world. Family businesses occupy one third of

Standard and Poor's 500 (Anderson et al., 2003). Family firms comprise 80% to 90% of all

business enterprises in

Family ownership is widely believed

to be less efficient than dispersed ownership. Fama and

Jensen (1983) argue that the combining ownership and control may allow founding

families to exchange profits for private rents. Demsetz (1983)

discusses that founding families may choose nonpecuniary

consumption and draw scarce resources away from profitable projects. Families also often choose CEO from the

pool restricted to family members, suggesting that difficulty to obtain

qualified and capable talent continuously, potentially leading to competitive

disadvantages relative to non-family firms (Anderson and Reeb, 2003).

Nevertheless, several excellent

companies in the world are family-owned firms. Salvatore Ferragamo, y182Εzfor example, has been

soundly managed in apparel industry without speculation or irrelevant

diversification. Samsung Electronics,

for example, has grown in semiconductor industries by aggressive

investment. Not only have case

studies of individual firms but also systematic empirical analyses found better

performance of family firms. McConaughy et al. (2001) find that

family firms have greater value, are operated more efficiently, and carry less

debt than non-family firms.

Anderson and Reeb (2003)

also find that family firms perform better than non-family firms.

There are several literatures

suggesting the benefits of family firms.

Demsetz and Lehn (1985) argue

that family members with large equity share have substantial economic

incentives to diminish agency conflicts and maximize firm value. James (1999) points out that families

have longer investment horizons, resulting in greater investment

efficiency. Stein (1988; 1989)

discusses how the presence of shareholders with relatively long investment

horizons can mitigate the incentives for myopic investment decisions by

managers.

As described above, existing studies

provide both advantages and disadvantages of family businesses, while empirical

analyses show better performance of family firms in the

The structure of this paper is as

follows: The next section briefly

reviews existing studies on family firms, and establishes several

hypotheses. Section III discusses

the data and the method. Section IV

shows the empirical results.

Section V discusses about the results and provides a summary and future

research agenda.

UDTheories and Hypotheses

It is widely believed that founding

families tend to take actions that benefit themselves at the expense of firm

performance. Fama and Jensen (1985) argue

that large shareholders employ different investment decision rules from

diversified shareholders, who are supposed to evaluate investments using market

value rules that maximize the value of the firms' residual cash flows.

Selecting CEO from the pool

restricted to family members can be another reason for poor performance of

family firms relative to non-family firms.

Schleifer and Vishny (1987) suggest that

large shareholders remain active in management even if they are no longer

competent and qualified to run the firm.

Families can also expropriate wealth

from the firm through excessive compensation, special dividends, and so

on. Shleifer and Summers (1988) argue that

families have incentives to redistribute rents from employees to

themselves. Family's action to

maximize their personal utility potentially results in poor firm performance

relative to non-family firms.

On the other hand, several

researchers point out the advantages of family firms. Demsetz and

Lehn y183Εz(1985) argue that families have strong

incentives to monitor managers and minimize the free rider problem inherent

with atomistic shareholders, because the family' wealth is closely linked to

firm welfare and because the family have knowledge of the firm's technology

necessary to monitor managers.

Families may be willing to invest in

long-term projects because they have longer horizons than other shareholders

(Stein, 1988; 1989; James, 1999).

Since founding families regard their firms as an asset to pass on to

their descendants rather than wealth to consume during their lifetime, firm

survival is an important concern for families. Therefore, family firms may maximize

long-term value (Casson, 1999).

Since existing literatures point out

both advantages and disadvantages of family firms, we set two alternative

hypotheses.

Hypothesis

1a: Family firms perform better

than non-family firms.

Hypothesis

1b: Non-family firms perform better

than family firms.

Supposing that we will find that

family firms perform better than non-family firms (consistent with Hypothesis 1a) like many existing

empirical studies, we will explore why family firms perform well. The disadvantages of family firms

pointed out by existing studies are broadly classified into two: prodigality or

divergence from maximization of firm value and incompetent and unqualified

managers chosen from the restricted pool of family members. This paper will examine the latter.

Founders may find it difficult to

choose a qualified successor from their family. Therefore, firms run by the

founders perform better than those run by the successors from their

family. If families understand such

a disadvantage, they may search for a talented manager from larger pool. As a result, they continue to own their

firms, but appoint CEO from outside the family. If so, family firms run by non-family

members perform better than those run by the successors from the family. Therefore, we set the following

hypotheses:

Hypothesis

2: Firms run by the founders perform better than those run by the successors

selected from the family.

Hypothesis

3: Family firms run by non-family members perform better than those run by

successors from the family.

Existing studies pointed out two

kinds of advantages of family firms: less agency conflict and longer investment

horizons. If combining ownership

and control, which mitigates agency conflict, is the reason for better

performance of family firms, firms not only owned by the families but also run

by the CEO from the family members should perform well. In the firms owned by the families but

run by CEO from outside the family members, however, ownership is separated

from management. Therefore, they

should not perform as well as the family firms combining ownership and

control. Thus, we have the

following hypothesis:

y184ΕzHypothesis 4: Family firms not only owned by the families but also

run by the CEO from the family members perform better than the firms owned by

the families but run by the CEO from outside the family members.

The reason for better performance of

family firms may be not combining ownership and management but large equity

share owned by family. Because the

families who are large shareholders have strong incentives to monitor managers

and mitigate agency problems, even firms owned by the family members with large

equity share but run by the CEO from outside the family members may perform

well. However this reason is not

applied only to family firms. Firms

owned by large but non-family shareholders should also perform well. Thus, we have the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis

5: Firms owned by large but non-family shareholders perform as well as family

firms.

If family firms have longer investment

horizons, they can invest in long-term project non-family firms cannot invest

in. As a result, family firms tend

to make more aggressive investment.

Moreover, non-family firms may adjust investment level to economic

conditions frequently, while family firms are patient enough to keep their

investment level. Therefore, we set

the hypotheses as follows:

Hypothesis

6: Family firms invest more than non-family firms.

Hypothesis

7: Family firms show more stable investment than non-family firms.

These hypotheses will be tested in

this paper to compare the performance between family and non-family firms, and

distinguish among the reason for the better performance of family firms.

VDData and Methods

(1)

Sample

In this study, we collected the data

of the electric machinery manufacturers in

Then, we collected the data of the

equity share of ten largest shareholders from Yuka Shoken Hokoku-sho of each firm. We regarded the shareholders whose

family name is the same as that of the founder, as founding family members, and

considered that sum of the equity share of founding family members is the

family shareR. Moreover, we examined if the current

president or chairman is the family y185Εzmembers.

Family businesses can be defined in

terms of management and in term of ownership. We have three kinds of family business

dummy variables. First, FB1 is equal to 1 if the president or

the chairman of the firms is from the founding family, and 0

otherwise. Second, FB2 is equal to 1 if family member is

listed in the top 10 shareholders, and 0

otherwise. Third, FB3 is equal to 1 if the equity share of

family among the 10 largest shareholders is more than 5%, and 0 otherwise. Out of 190 sample firms, 69 firms are

run by the founding family (FB1=1),

80 firms are owned by the family (FB2=1), and 51 firms are largely owned by the

family (FB3=1).

(2)

Variables and Methods

First, to know if there is

significant difference in performance between family and non-family firms (Hypothesis 1a and 1b), we will

perform t-tests for difference in means of performance. As performance measures, we construct

the return on asset (ROAt) and the sales growth

rate (AAGRt). ROAt is the average of ROA of

a firm in each year during the period t, and AAGRt is the average annual

growth rate of the sales during the period t. We set the three periods: from 1992 to

2005 (whole sample period), from 1992 to 1998 (depression), and from 1999 to

2005 (recovery)S.

Second, we will examine if the

selection of the top management from the pool restricted to the family members

causes a disadvantage of family firms.

To do so, we will divide the family firms run by founding family members

(FB1=1) into those run by the

founders and those run by the successors of family members. Then, we will perform t-tests for

difference in means of performance between the two (Hypothesis 2). If

restricted pool causes a disadvantage, we expect that family firms run by the

founder perform significantly better than those run by the successors of family

members. We will also divide family

firms into those run by the successor of family members (FB2=1 and Successor) and those run by non-family members (FB2=1 and FB1=0), and will perform t-tests for difference in means of

performance (Hypothesis 3). If restricted pool causes a

disadvantage, we expect that family firms run by non-family members perform

significantly better than those run by the family members.

Third, we will examine if combining

ownership and control is the advantage of family firms. To do so, we will perform t-tests for

difference in means of performance between family firms not only owned by the

families but also run by the CEO from the family members (FB2=1 and FB1=1) and the

firms owned by the families but run by the CEO from outside the family members

(FB2=1 and FB1=0) (Hypothesis 4).

Fourth, we will examine if not

combining ownership and management but large equity share resulting in strong

incentive to monitor managers is the advantage of family firms (Hypothesis 5). To do so, we will run the

regressions. Dependent variables

are several kinds of performance measure described above. Independent variables are dummy

variables of family firms owned by family members (FB2) and equity share of the largest shareholders (Largest_Share). If not being owned by family members but

being owned by large shareholders is the reason for better performance, Largest_Share as well

as FB2 y186Εzshould have significantly

positive coefficient We will also

include several control variables described below.

Finally, to examine any impacts of

ownership structure on investment behavior, we will run the regressions. As dependent variables, two kinds of

investment, R&D investment (RDRt and CVRDRt) and

capacity investment (CAPRt and CVCAPRt), will

be examined. RDRt is the

average of R&D sales ratio of a firm in each year during the period t, and CAPRt is the

average of capacity investment divided by sales of a firm in each year during

the period t (t=1994-2005, 1994-1998, 1999-2005). CVRDRt is the

coefficient of variation of R&D sales ratios in each year during the period

t and CVCAPRt is the

coefficient of variation of capacity investment divided by sales in each year

during the period t.

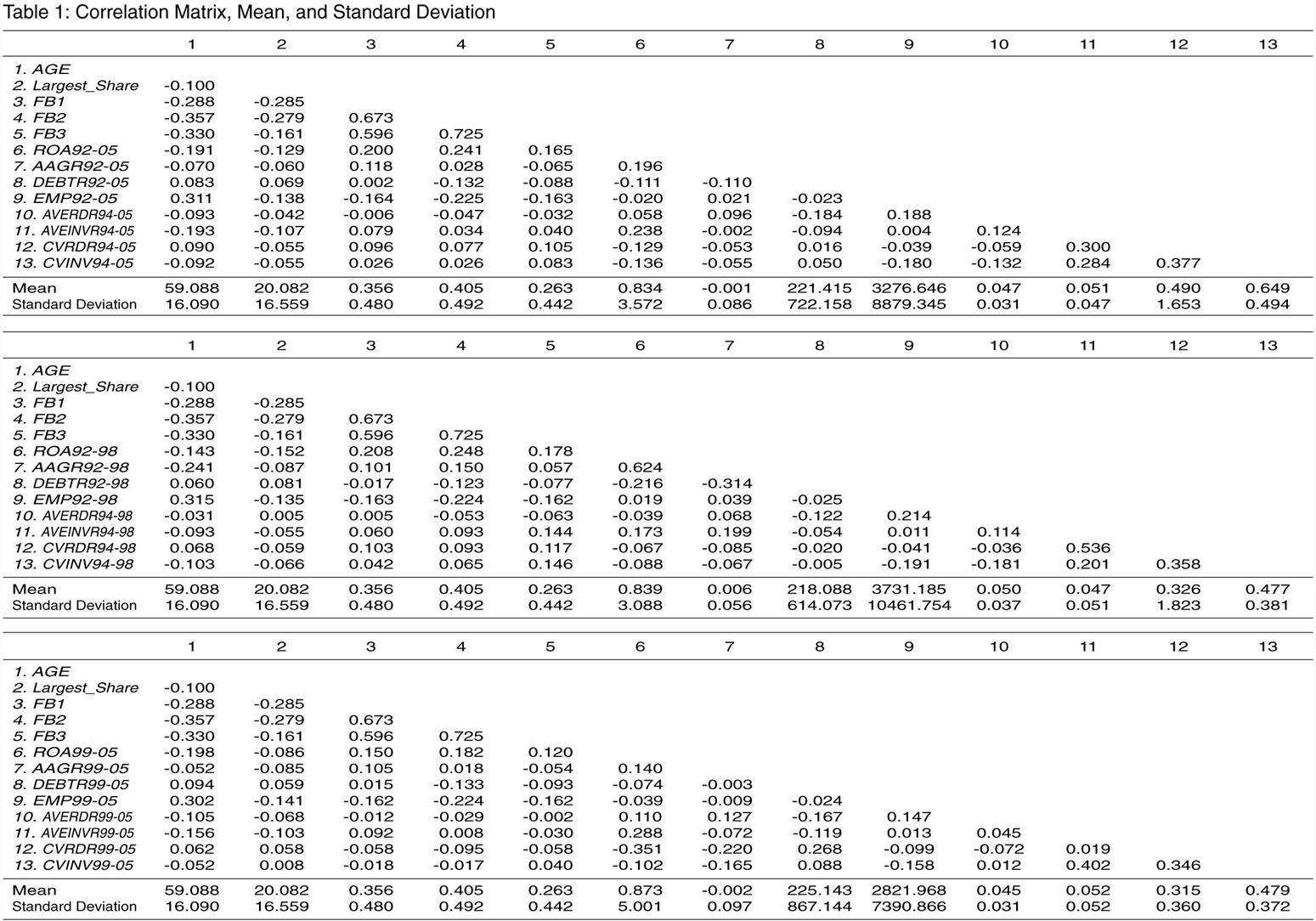

Independent variables are family firm

dummies such as FB1, FB2, and FB3. In addition to

them, we will include several control variables. AGE is the number of years from the year when the firm was

established to 2005. DEBTR is debt ratio. EMP

is the number of employees, which stands for the size of the firm. We also include ROAt and Largest_Share. The mean, standard deviation, and

correlation matrix of the variables are indicated in Table 1.

y187Εz

y188Εz

WDResults

(1)

T-Test

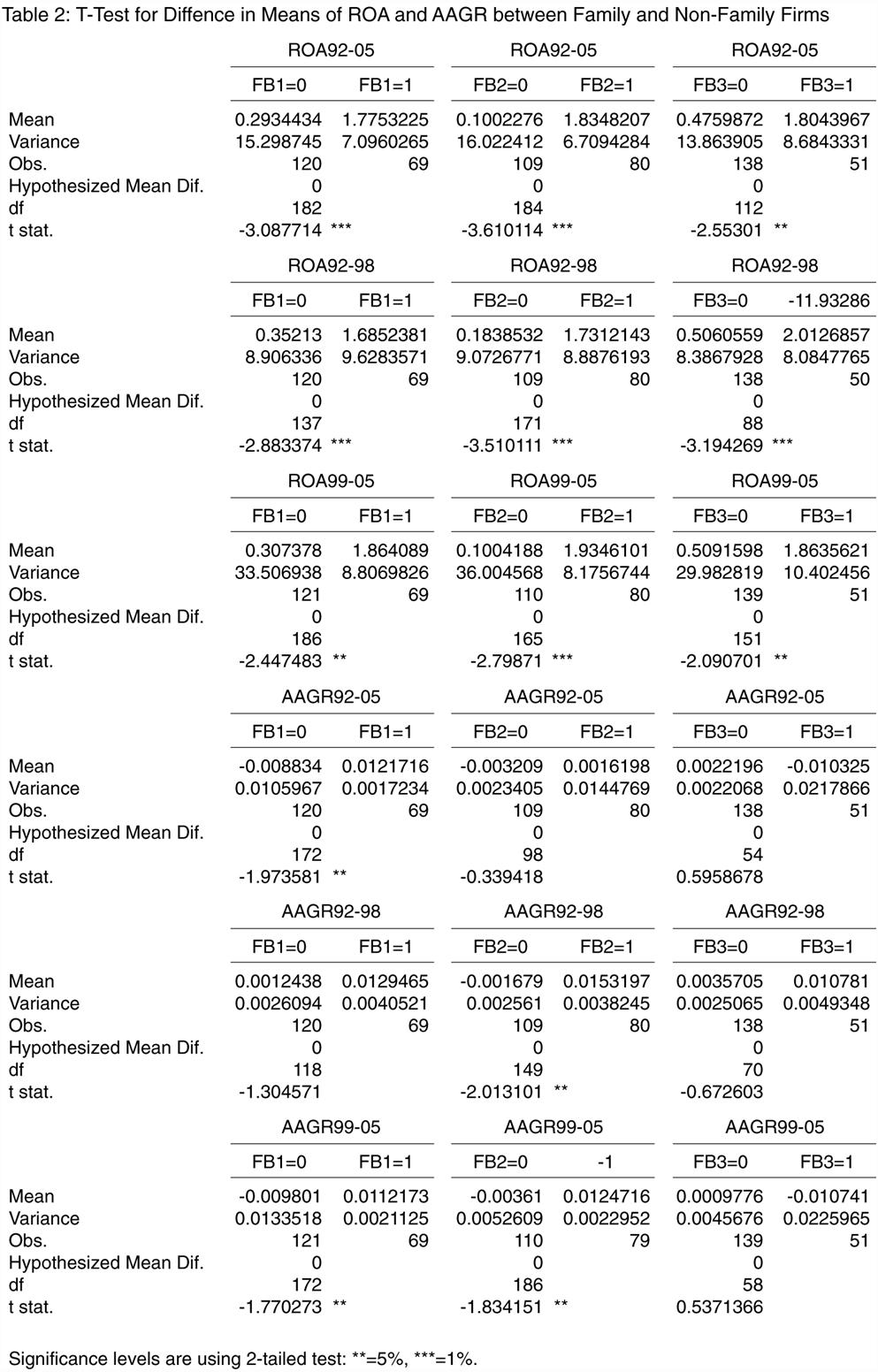

First, the results of the t-tests for

difference in means of performance between family and non-family firms are

shown in Table 2. Regarding ROA, any

kinds of family firms perform significantly better than non-family firms. Regarding sales growth rate, the results

are mixed. The firms run by the

family members (FB1) grow

significantly more than non-family firms from 1992 to 2005 and from 1999 to 2005,

but the difference in growth rate from 1992 to 1998 is insignificant. The firms owned by the family members (FB2) grow significantly more than

non-family firms from 1992 to 1998 and from 1999 to 2005, but the difference in

growth rate from 1992 to 2005 is insignificant. The firms owned by the family members

with more than 5% of equity share (FB3)

do not grow significantly more than non-family firms during any periods. Thus, Hypothesis 1a is clearly supported in terms of ROA, and partially

supported in terms of sales growth rate, while Hypothesis 1b is rejected.

In sum, in the Japanese electric machinery manufacturers, family firms

perform better than non-family firms as the existing empirical analyses in the

different contexts found.

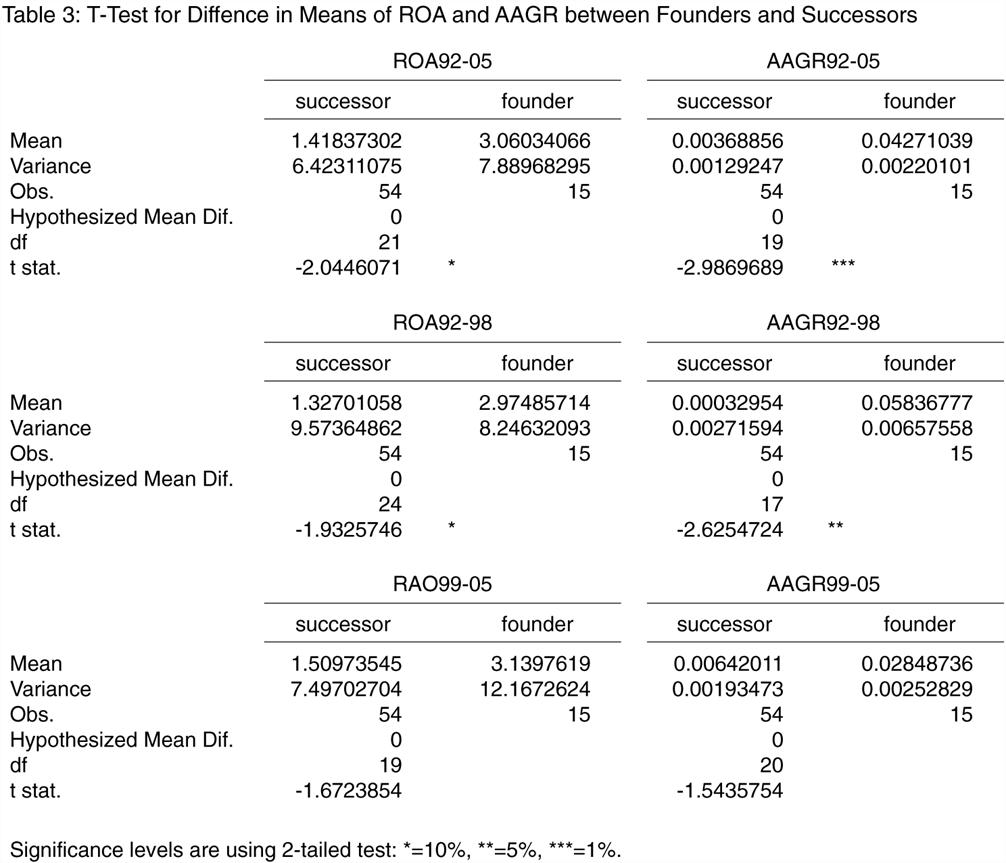

Second, the results of the t-tests

for difference in means of performance between family firms run by the founders

and those run by the successors are shown in Table 3. In terms of ROA as well as sales growth

rate, family firms run by the founders perform better than family firms run by

the successors from 1992 to 2005 and from 1992 to 1998. Therefore, during these periods, Hypothesis 2 is supported. This suggests that the family may have

difficulty to obtain qualified and capable CEO from the pool restricted to the

family members.

However, the difference in

performance may not be caused by the difference between founders and

successors. Family firms run by the

founders are relatively young. Therefore,

better performance of the family firms run by the founders may be caused not by

the difference in top management (founders vs. successors) but by the

difference in youth. Insignificant

difference in performance from 1999 to 2005 when age difference between the two

kinds of firms relatively decreases is consistent with the latter

interpretation.

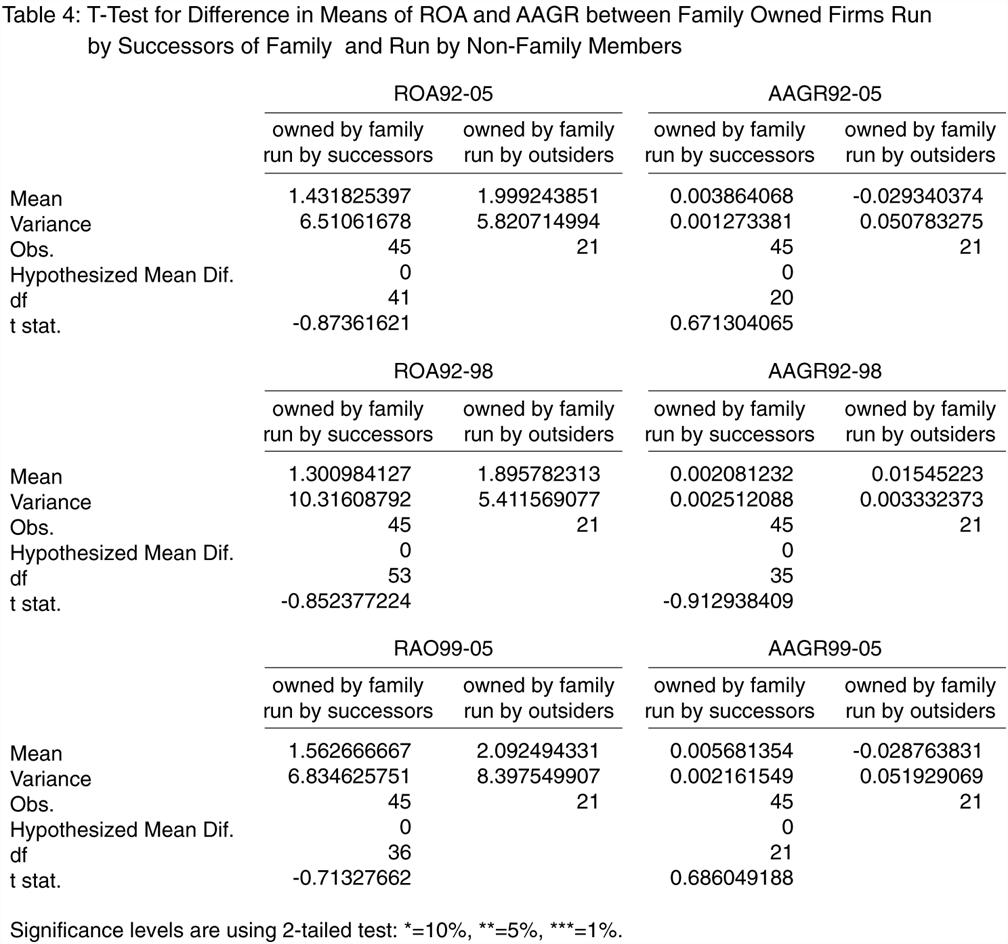

The results of another test examining

if selection of managers from restricted pool of family members is the

disadvantage of family firms are indicated in Table 4. Different from the results in Table 3,

any specifications in Table 4 do not show significant difference. That is, there is no significant

difference in performance between family owned firms run by the successors from

family members and those run by non-family members. Thus, Hypothesis 3 is rejected.

Expanding the pool of managers to outside families does not improve

performance. This suggests that the

pool restricted to the family members does not cause disadvantages of family

firms.

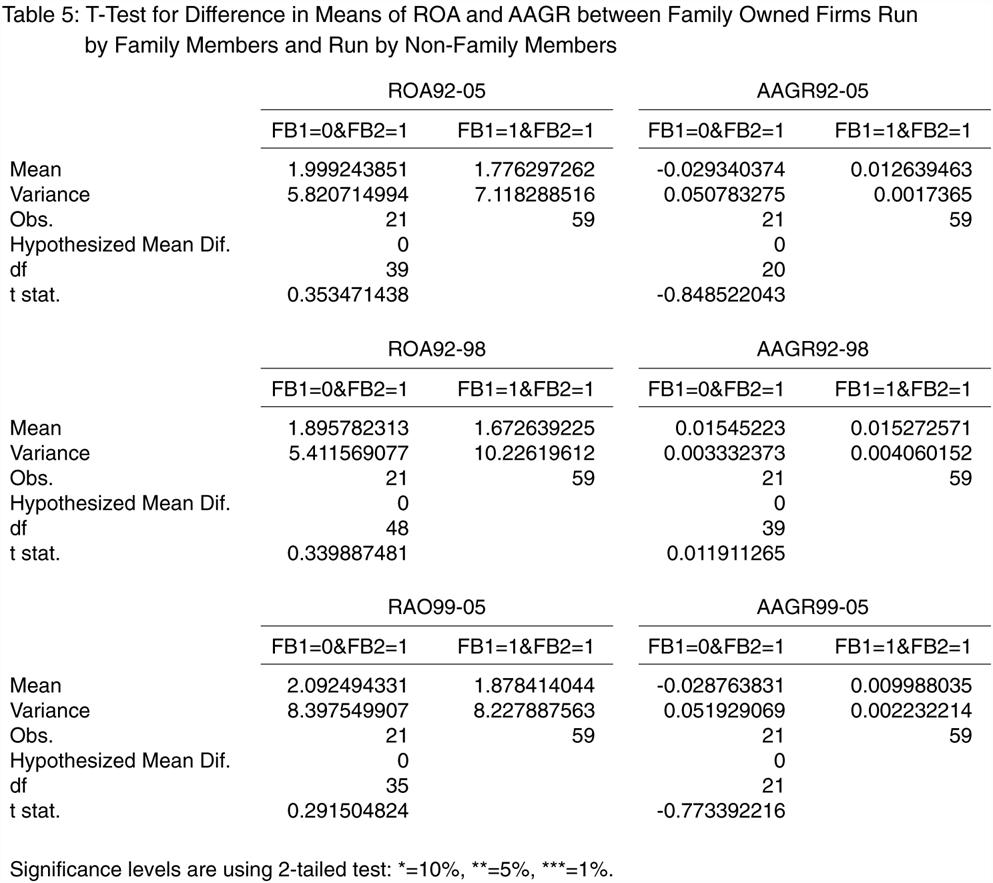

Third, we performed several tests to

examine if combining ownership and control is the reason for better performance

of family firms. One is the t-tests

for difference in means of performance between firms owned by family and run by

family members (FB2=1 and FB1=1) and firms owned by family but run

by non-family members (FB2=1 and FB1=0). The results are shown in Table 5. Any specifications in Table 5 do not

show significant difference. That

is, there is no significant difference in performance between family owned

firms run by the family members and those run by non-family members. Thus, Hypothesis 4 is rejected.

y189Εz

y190Εz

y191Εz

y192Εz

y193Εz

(2)

Regression Analysis

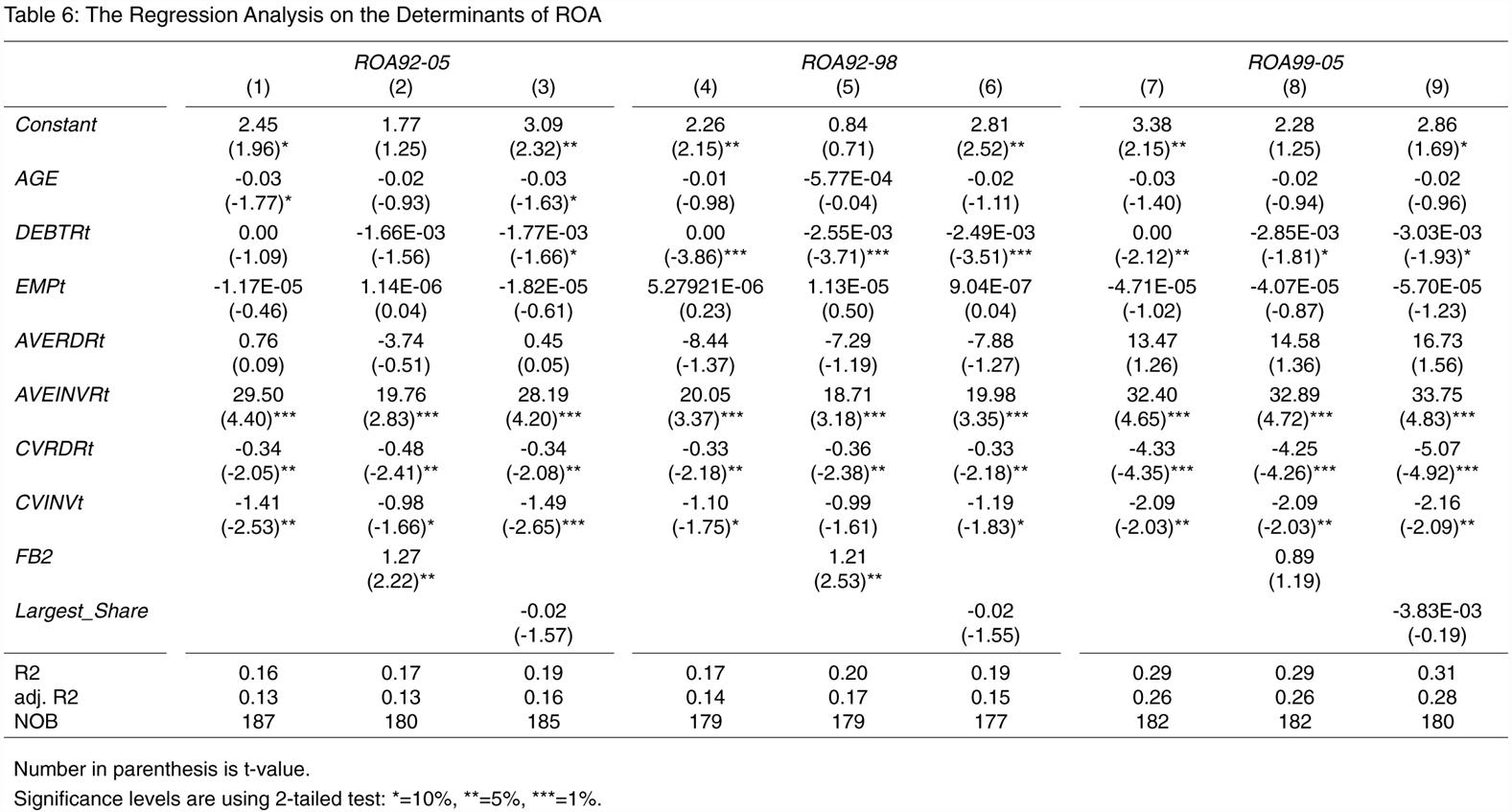

We ran the regressions to examine if

large shareholders' strong incentives to control managers are the reason for

better performance of family firms.

The results are indicated in Table 6 and 7. According to the tables, the

family business dummy (FB2) has

significantly positive relationship with ROA92-05

and with ROA92-98, while does not

have significant relationship with ROA99-05 and with sales growth (AAGRt) during

any periods. Therefore, family

firms show higher ROA from 1992 to 2005 and from 1992 to 1998 than non-family

firms. On the other hand, the

coefficient of Largest_Share in any models is

insignificant in almost all of the models.

In model (9) in Table 7, it is significant but the sign is negative and

opposite to our

expectation. Therefore,

shareholders with large equity share do not have a positive impact on firm

performance, and Hypothesis 5 is

rejected. That is, family firms perform

better because family with large equity share has strong incentives to monitor

managers, while all the large shareholders do not work equivalently. This suggests that not owning large

equity share but family membership does matter.

According to Table 6 and Table 7,

some of the variables indicating investment behavior have significant

coefficients. In all the models of

Table 6, capacity investment (AVEINVR)

has significantly positive coefficients and stability of R&D investment and

that of capacity investment (CVRDRt, CVINVt) have

significantly negative coefficients.

In model (3) through (6) of Table 7, AVEINVRt has a

significantly positive coefficient and CVRDRt has a

significantly negative coefficient.

In model (7) through (9) of Table 7, AVERDRt has a

significantly positive coefficient and CVRDRt has a

significantly negative coefficient.

Therefore, in short, the more the firms invest and the less they change

the amount of investment, the better they perform.

Then, we examined if there is any

difference in investment behavior between family and non-family firms. The results are shown in Table 8, 9, 10,

and 11. Table 8 indicates the

result of the analysis on R&D investment. In model (8), FB2, the dummy for family firms, where family members are listed in

the top 10 shareholders, has significant at the 10% level, but the sign is

negative. In the other models, any

family firm dummies are not significant.

Therefore, family firms do not invest in R&D more than non-family

firms.

In Table 9 indicating the result of

the analysis on capacity investment, on the other hand, FB2 and FB3, dummies for

the firms owned by the family members have significantly positive coefficients

from 1994 to 1998, while they have significantly negative coefficients from

1999 to 2005. Thus, family firms

invest in capacity more than non-family firms from 1994 to 1998, while family

firms invest in capacity less than non-family firms from 1999 to 2005. Hypothesis

6 is supported only in case of capacity investment from 1994 to 1998.

Table 10 shows the results of the

analysis on stability of R&D investment. In models (1) through (6), all the three

kinds of family business dummies have significant coefficients, but the sign is

positive. In Table 11, showing the

results of the analysis on stability of capacity investment, FB3 has a significant coefficient only

in model (4), but the sign is positive.

The positive sign is opposite to our expectation, suggesting that family

firms change the amount of R&D and capacity investment more than non-family

firms. In other models, family

business dummies do not have significant coefficients. Therefore, Hypothesis 7 is rejected.

y194Εz

y195Εz

y196Εz

y197Εz

y198Εz

y199Εz

y200Εz

XDDiscussion and Conclusion

This paper examined if family firms

perform better than non-family firms and explored what are the advantages of

family firms, using the data on the Japanese electric machinery

manufacturers. We found that family

firms show higher profitability than non-family firms. This is consistent with the existing

empirical analyses in different contexts.

It is often pointed out that

selecting top management from the pool restricted to the family members is the

disadvantage of family firms. We

found that family firms run by successors from the family members perform worse

than those run by the founders. But

we did not find any significant difference in performance between family firms

run by the successors and those run by non-family managers. Therefore, whether managers are

appointed from the restricted pool or not does not matter. This suggests that better performance of

the founders may be caused by the youth of the firms, and that restricted pool

of managers is not the important disadvantage of family firms.

It is also argued that combining

ownership and control mitigates agency conflicts and is the advantage of family

firms. However, we found no

significant difference in performance between firms own by and run by family

members and those owned by family but run by non-family members. This suggests that combining ownership

and control is not the advantage of family firms. Similarly, it is often pointed out that

founding family with large equity share has strong incentives to monitor managers, therefore, family firms

perform better. However, we found

no significantly positive impact of the equity share of the largest

shareholders on performance.

That is, large equity share by itself does not strengthen monitoring

managers.

Other studies pointed out that longer

investment horizons of the family are the advantage of family firms. We found family firms invest in capacity

significantly more than non-family firms from 1994 to 1998, while we did not

find the evidence supporting the hypothesis during other periods or in terms of

R&D investment. We did not also

find the evidence supporting the hypothesis in terms of stability of

investment. However, R&D

investment does not have significantly positive impacts on performance in the

regression analyses reported in Table 6 and Table 7. That is, R&D investment is not a

significant determinant of firm performance in our data, therefore, it is not

strange to find insignificant results for R&D investment.

Moreover, taking it into account that

Japanese economy did not grow in the 1990s while it has recovered in 2000s, the

findings above can be interpreted in the following way. When economy is growing, firms invest in

capacity whether they have long horizon or not. Therefore, we did not find a significant

difference in investment behavior between family and non-family firms.

When economy is stagnant, on the

other hand, firms invest differently depending upon horizon they have. Firms, which are concerned with

short-term performance, should decrease capacity investment to recover

profitability. On the other hand,

firms with long horizon may be patient enough to invest a lot in capacity in

spite of low profitability. If so,

family firms may invest in capacity aggressively even when economy is stagnant

since they have long horizon, and because of such investment behavior, they may

perform better. In sum, family

firms have advantage of long horizon, which makes the behavior of family firms

different from that of non-family firms especially during low growth period.

y201ΕzThere are several future

research agenda. First, in this

study, we defined family firms in terms of management and in terms of

ownership. In terms of management,

the criterion is whether the president or the chairman of the firm is from the

founding family. However, not only

the president or the chairman is influential, but also the family members in

the board, could influence on firms performance. Therefore, we need to examine family

firms in more detail. Second, this

is a single industry study. We will

collect the data of other industries and see if there is any difference among

industries and if we can generalize our findings. Third, we examined only R&D and

capacity investment and stability of them as investment behavior. However, to examine the effect of long

horizon, we need to examine other investment such as diversification, global

expansion, and so on.

References

Berle, A. and Means, G., 1932, The Modern Corporation and Private

Property,

Casson, M., 1999, gThe Economics of

the Family Firm,h Scandinavian Economic

History Review, 47: 10-23.

Demsetz, H., 1983, gThe Structure of

Ownership and the Theory of the Firm,h Journal

of Law and Economics, 25: 375-390.

Demsetz, H. and Lehn, K., 1985, gThe

Structure of Corporate Ownership: Causes and Consequences,h Journal of Political Economy, 93:

1155-1177.

Fama, E. and Jensen, M., 1983,

gSeparation of Ownership and Control,h Journal

of Law and Economics, 26: 301-325.

James, H., 1999, gOwner as Manager,

Extended Horizons and the Family Firm,h International Journal of the Economics

of Business, 6: 41-56.

McConaughy, D. L., Matthews, C. H.,

and Fialko, A. S., 2001, gFounding

Family Controlled Firms: Performance, Risk, and Value,h Journal of Small Business Management, 39: 31-49.

Schleifer, A. and Summers, L., 1988, gBreach of

Trust in Hostile Takeovers,h in A. Auerbach, ed., Corporate Takeovers: Causes and Consequences,

Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R., 1997, gA Survey of

Corporate Governance,h Journal of Finance,

52, 737-783.

Stein, J., 1988, gTakeover Threats

and Managerial Myopia,h Journal of

Political Economy, 96: 61-80.

Stein, J., 1989, gEfficient Capital

Markets, Inefficient Firms: A Model of Myopic Corporate Behavior,h Quarterly Journal of Economics, 103:

655-669.